Interpreting for foreign language courses:

A case study with Spanish1

David Quinto and David Bar-Tzur

Created 24 May 1999, links updated monthly with the help of LinkAlarm.

Nosotros estamos aquí: !Óyenos!1

Nosotros estamos aquí: !Óyenos!1

Preparation

The task of interpreting for foreign language classes is difficult enough without having a previous knowledge of the language being taught. The interpreter really should have had at least two years of instruction in the foreign language he or she will interpret, even for an introductory course in that language. It may have been years since you used the foreign language you learned in high school, but with some preparation before each class it will come back to you. If you start by interpreting the first introductory course, you will relearn it with ease. As a last resort, interpreters with no knowledge of the language can start by interpreting an introductory course and work their way up. Increasing numbers of interpreters have a third language, besides ASL and English, and we believe that a third language, whether it's a spoken language or a signed language, is certainly an asset in today's world.

Having the textbook for the class is essential. By following the syllabus and reading ahead, the interpreter can know which aspects of the language and which vocabulary items will be dealt with in class on any given day. Bringing the book to class can be helpful in a number of ways. If the teacher asks a question from the book without mentioning the number of the question, by checking your copy of the book you can tell them where to read, instead of laboriously fingerspelling the question which they may get faster by reading it in the text. If the students are reading aloud an extended passage from the book, it may be beneficial to let the deaf students know where the class is in the textbook and have them read along. Some (hearing) students are difficult to understand when they read Spanish or speak it: having the book turned to the right page will help you decipher their attempts at pronunciation.

Doing the homework is also very helpful, especially if the language is new to the interpreter or has been unused for several years. If the interpreter does not wish to purchase the textbook and cannot get a copy from the teacher or library, it is possible to order a desk copy (free copy for educators) by writing to the publisher. If that doesn't work, xerox the pages you need, use an old Spanish text, or borrow the teacher's text at a regular time when you are free and the teacher is busy with other things. Consider tutoring or working together with the student if you are reasonably competent in the language. If you are just now learning Spanish with the class you can still use the time to figure out together how Spanish works and what the student thinks would work best for her/himself in terms of representing the language (i.e. using ASL, PSE, Cued Speech, etc).

Every language has a slightly different phonology or way to pronounce its letters. The interpreter needs to find out what the students want from their course. Do they want to learn how to pronounce, speechread, or only read and write the language? This is a good discussion to have with the teacher present, so that s/he can become aware of what modifications might need to be made. This will bring up the broader questions of how the deaf student should recite: using voice, fingerspelling everything, some sign and some fingerspelling, or Cued Speech.

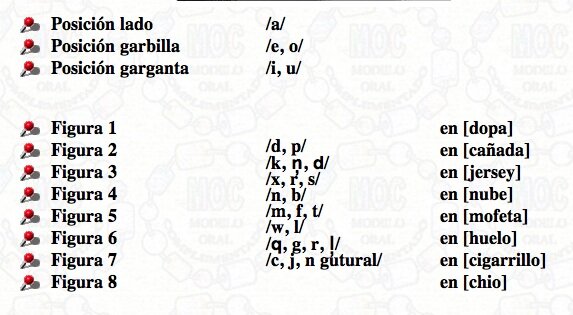

Cued Speech could come in very handy for representing a foreign language if the consumer knows it or is willing to learn it, since it represents the pronunciation (and the individual words) in a way that the eye can take in, rather than fingerspelling every word. As mentioned above, phonologies differ, so special cueing systems have been developed to represent phonemes that do not exist in English. Spanish examples are j, ll, r, rr, and x.

|

|

One more avenue for learning Spanish is a teaching method using computers which is generally referred to as CALL (Computer-Assisted Language Learning). Also, other specific programs have been developed with their own names. If such programs are available at the school where the foreign language is being taught, the teacher may be able to give the deaf person guidance on how to use the computer programs to good effect, since they serve to promote reading and writing, rather than working through an auditory mode. See the bibliography for some articles on this methodology.

An exciting recent development has been the blossoming of awareness about foreign sign languages. We look forward to the day that Deaf people can receive academic credit for learning these sign languages as well. It may be beneficial to skim a sign language from the country whose spoken language you are interpreting. Consult with the Deaf person to see if they wish you to use foreign signs to represent some of the frequently ocurring words in the foreign spoken language they are learning. However, they may wish to see the signed language of a specific country. Spanish is spoken in many countries (such as Spain, Mexico, and Puerto Rico), so you would need to decide which country's sign language you would want to borrow from and be able to find such a sign book.

Foreign countries, especially if they have a strong contingent that supports oralism, may have an invented system (parallel to Manual Codes for English) to represent their spoken language. If this is to be used, it requires that you and the Deaf person work with a language or system that may be unfamiliar to both of you while trying to learn the foreign language with the rest of the class!

Most interpreters for foreign language classes whom I have interviewed said that they used unvoiced Sim-Com, that is mouthing (in our case) Spanish while simultaneously using conceptually accurate ASL signs and fingerspelling. The method you decide to use should be negotiated with your consumer. If there is no one-to-one match between English and ASL, which share some of the same culture, imagine trying to find one ASL sign for a given Spanish word! This is where sign negotiation comes in.

Spanish letters

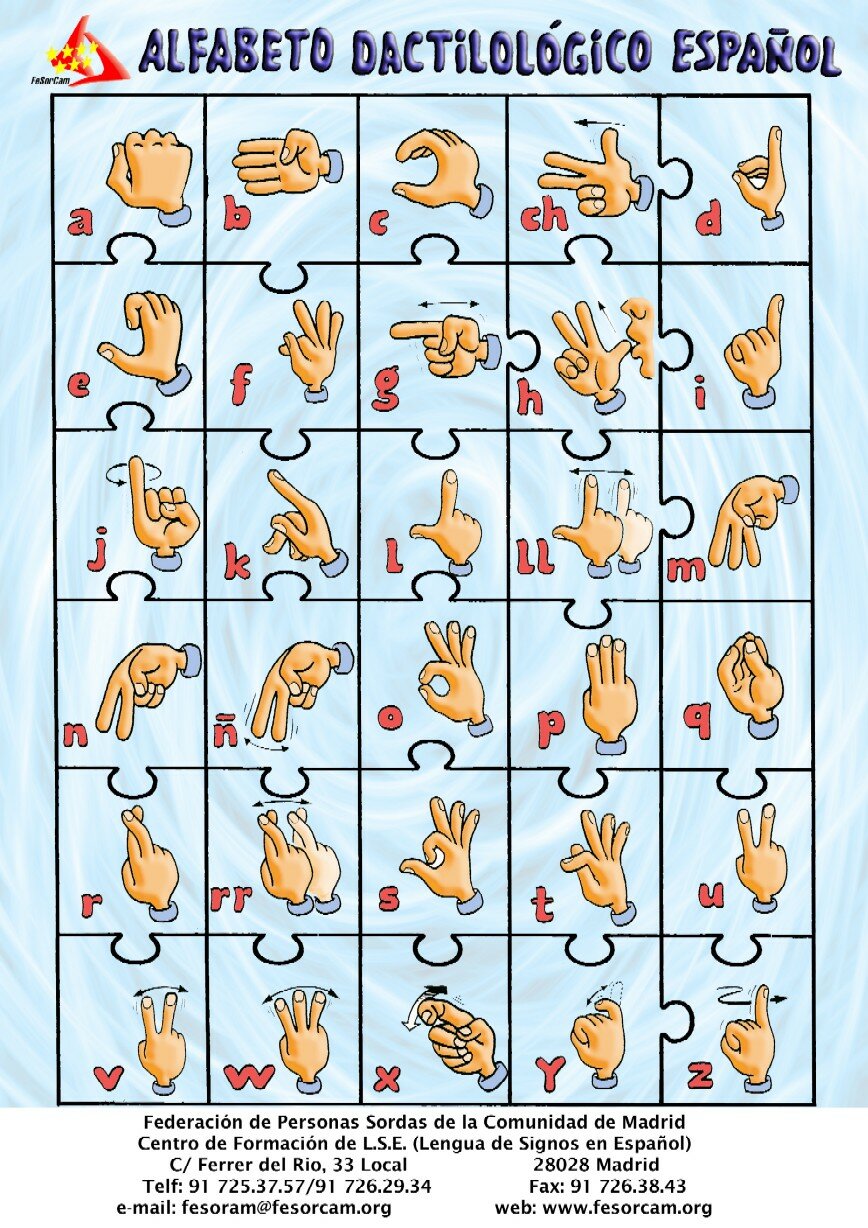

Above you can see a chart of Spanish fingerspelling. You can see that many of the letters that exist in English as well look different than ASL: b, e, f, g and so on. The dipthongs (letter combinations) that don't exist in English are ch, ll, ñ, and rr. Except for ñ, these could be fingerspelled, but the Spanish fingerspelling may prove helpful if the deaf student wants to learn pronunciation, since these are not simply pronounced like the commponent letters. Moreover, Spanish has additional letters through the addition of diacritical marks - á, é, í, ó, ú, and ü. Some decision needs to be made about how to represent these letters. Furthermore, it would be helpful to review the rules for accent marks (diacritical marks) on a regular basis and possibly even have a chart that can be used as reference during the actual interpreting.

Fingerspelling every word would definitely represent Spanish exactly and would probably be the best way to teach Spanish. David Bar-Tzur has observed Larry Lomaglio do an outstanding job using this method at NTID. But when you are interpreting, you can't control the pace, and fingerspelling without some sign support would not be feasible. Excessive fingerspelling could lead to a Cumulative Trauma Disorder (such as Carpal Tunnel Syndrome). In addition, it is just too much for most Deaf people's eyes and the interpreter's hands. However, it is still necessary to fingerspell at least some words as shall be discussed below.

One last thought in terms of Spanish words and fingerspelling: if a Spanish word has an English cognate, it may be helpful to add that information as a side comment during the interpretation (such as SPANISH, ENGLISH, FINGERPELL SAME PLUS MEAN SAME). Similarly, if a word is a false cognate, let the students know this so they can use the word correctly. Some examples of false cognates are "realizar" ("to accomplish or succeed" as opposed to "to realize"), and "embarazada" ("pregnant" as opposed to "embarrased").

Fingerspelled words

Here is a guide to some of the words that we find are helpful to fingerspell. For all sentences we would emphasize that one should mouth the Spanish: it emphasizes to the students that Spanish is being represented, not English; it may remind the students of some of the Spanish words, if they can speechread them; and it helps the interpreter attend to finding lexical equivalents for Spanish and ASL (no easy task!)

(1) Words that are being introduced for the first few times - "¿Cómo te llamas?" or "¿Qúe es tu nombre? ("What's your name?") = C-O-'-M-O T-E LL-A-M-A-S? Later when the focus is off "¿cómo te llamas?" and these words have been learned, you could replace the fingerspelling with signs (YOUR NAME?) while mouthing the Spanish.

(2) The conjugation of verbs should be reinforced through fingerspelling. For example, in the following conjugation drill:

Yo amo, tu amas, el/ella ama, Usted ama, nosotros/as amamos, vosotros/as amais, ellos/as aman, Ustedes aman [I love, you (informal) love, he/she loves, you (formal) love, we love, you (group) love, they love, you (group) love]the underlined portions of the verb (i.e. the part of the word that changes with the conjugation), can be emphasized by setting up a system to represent the speed and manner in which the drill is being recited. One possible way to do this would be to use the 5-CL handshape with the palm orientation toward the body (as in the description of a list) and each finger (or element of the list) would represent the different conjugation reference. For example, the "yo" ("I") form would be fingerspelled close to the thumb, the "tu" ("you" informal) would be fingerspelled close to the index finger, the "el/ella'' ("he/she") form would be fingerspelled close to the middle finger and so on. At first, the entire verb could be fingerspelled and as time goes on and the drill speeds increase, the entire verb could be fingerspelled at the beginning and then the changed ending could be represented close to each finger (just as before) always keeping in mind that the entire word is on the mouth. In general, it is a good idea to pay extra attention to the conjugation of verbs. A basic understanding of conjugations would greatly increase the success of the interpretation.

(3) Fingerspell and sign the substituted words in a substitution drill. An extra emphasis may be added when fingerspelling the article if the gender of the noun has changed during the drill. For instance, in a typical verb conjugation drill, both masculine and feminine verbs are used. A good practice would be to somehow emphasize the change from one gender to the other so the deaf student could be aware of it. In addition, it would be a good idea to set up the elements of a drill in two different areas in the signing space. If the teacher is doing a drill with an article and a noun, the article can be signed to the left and the noun to the right (or the distinction could be made with a simple body shift). This would serve to help distinguish the two words being signed. For example, in a typical drill the articles E-L (masculine "the") and L-A (feminine "the") could be signed with a slight body shift to the left while the nouns can be signed with a body shift to the right (or vise versa) A typical substitution drill is as follows (with teacher cue and student response): T(eacher): coche, S(tudent's response): el coche. T: silla, S: la silla. T: árbol, S: el árbol. T: cama, S: la cama. T: mesa, S: la mesa. T: plato, S: el plato.

(4) Fingerspell and sign words that are being used in an idiomatic way - " ¿Qúe pasa?" means "what's up?" so the interpreter would sign Q-U-'-E P-A-S-A?, WHAT'S-UP?

(5) Fingerspell more of a given sentence to reinforce old ideas when there is extra time. A particularly good time for this is when the teacher says a sentence and the class is supposed to repeat it, or when students are slowly responding to a question from the teacher. It may be that as the students get more advanced, they can tolerate more fingerspelling in the foreign language and may need it to break away from thinking in ASL or English and think instead in the fovign language itself.

Adding suffixes/prefixes to the root verb

Spanish verb formation differs from that of English and ASL. A prefix or suffix that is added to a verb can add negation, specify the pronoun, and accomplish other semantic changes as well. For example, "arreglar" means to "plan", "arrange" or "fix" something. When the prefix "de" is added, the word "desarreglar" is created which means to "fall apart", "become disorganized", or "break-down". In addition, if you were to add the suffix "se", the new word, "desarreglarse" would also include the pronoun. Thus, the meaning of the new word is that "something is disorganizing itself" or "something is breaking itself down". A possible way to sign that (including the fingerspelled word) would be: D-E-S-A-RR-E-G-L-A-R-S-E, ITSELF BREAKDOWN. The possibility of changing the meaning of the root verb several times by adding a suffix or a prefix is common in Spanish. Be aware of this because it makes the interpreting task more challenging. Something that is said in Spanish using one word most be interpreted into ASL using several signs.

Conjugations and tenses of verbs

It is very helpful to understand the conjugations and tenses of Spanish verbs before you attempt to interpret, because a great deal of class time is taken up learning and discussing them. Perhaps the creation of a chart which maps out the different manners as well as tenses could be a good study guide before the interpreting assignment and even serve as reference sheet during the actual assignment if a confusion would arise.

Working with the students

As mentioned before, find out the goal(s) of the students in learning the foreign language: do they want to be able to speechread native speakers, write and read only, or also be able to pronounce the language? Remember to negotiate signs, how much fingerspelling is desired, and how will the students represent the answer to questions from the teacher - will they fingerspell the sentence, use voiced or unvoiced Sim-Com, Cued Speech, or some other option? The student may know the noun and verb endings correctly, but the interpreter should beware of unconsciously using cloze skills to fill in what the answer should be. If the students are not interested in speechreading or speaking the language, pronunciation drills will not be helpful in themselves, so perhaps the time could be used to merely spell out what the class is saying and interpret it, to give the students more exposure to the language.

Another method that has been used where the interpreter works even more closely with the student is to use a laptop computer to "caption" the class. The interpreter types the drills and dialogue. The student and the interpreter can then practice the drills by typing on the laptop while the other students practice orally. At the end the session can be printed and saved for further study.

A related method is to use a voice recognition system. The teacher wears a microphone and their speech is translated into text on a computer screen. One drawback is that the present state-of-the-art requires the person whose speech will be transcribed to spend many hours training the computer to become accustomed to their voice and will therefore require extra work from the teacher (as much as 15 hours). The system also can not transcribe spoken text from audiotapes or videotapes that might be used to supplement the hearing students' auditory training unless similar session are used to accustom the computer again. The computer will aso make some transcription mistakes that will have to be corrected later. Voice recognition programs dedicated to the language in question may be necessary to show diacritical marks. On the positive end, it will allow the interpreter to use their hands for interpreting so that they will not be flitting from keyboard to ASL or falling behind in the lecture and will lessen repetitive motion problems.

Working with the teacher

It is essential to be a team player with the teacher, and in foreign language classes it is inescapable. Show your interest in doing the readings and homework, so that the teacher will realize early that the task of interpreting is more than a lexical skill like taking dictation. Some language classes use TPR (total physical response), where commands are given in the language, like "!Párense!" ("Stand up!") or "!Siéntense!" ("Sit down!"). For such situations, one strategy would be to interpret first and then fingerspell so that the deaf student is able to perform the action simulaneously with the hearing students.

If students pair up for spoken dialogues delivered during a later class period as homework, the teacher might simply give the deaf students more written work as a substitute. If there is an auditory comprehension part to the tests, where the students listen to an audiotape and answer questions on what they have heard, the teacher could have an additional written part for the deaf students' test. If there is group work and there is only one deaf student, ask the teacher if it is best to interpret for a hearing partner or if the interpreter should work with the student.

Summary

Interpreting for a foreign language course presents a number of interesting challenges for the interpreter, but by working with the teacher and students and preparing well for each class, it can be made to work. The teacher will have an opportunity to use creativity in redesigning some materials for the deaf students as well as to be exposed to yet another language (ASL) which may make them think more deeply about the relationship of language and culture. The interpreter will firm up his/her skills in the foreign language being taught and intercultural mediation. Furthermore the deaf students will be able to gain access to a foreign language that will broaden their way of thinking about the world.

Books and articles

Books and articles Adams, M. G. Historia de la educacion de los Sordos en Mexico y Lenguaje Por Senas Mexicano (History of the education of the Deaf in Mexico and Mexican Sign Language.) Dawn Sign Press. ISBN: 159352008-5. In an effort to encourage greater understanding of Mexican Deaf culture and to bring attention to the need for better education and training for the deaf in Mexico, Margarita Adams, who was born deaf in Mexico City, wrote Historia de la educacion de los Sordos en Mexico. Education of the deaf in Mexico has been spotty and severely underfunded by the government, condemning generations of deaf children to little or no schooling and illiteracy. Historia features 158 pages of Mexican signs with Spanish and English language keys.

Adams, M. G. Historia de la educacion de los Sordos en Mexico y Lenguaje Por Senas Mexicano (History of the education of the Deaf in Mexico and Mexican Sign Language.) Dawn Sign Press. ISBN: 159352008-5. In an effort to encourage greater understanding of Mexican Deaf culture and to bring attention to the need for better education and training for the deaf in Mexico, Margarita Adams, who was born deaf in Mexico City, wrote Historia de la educacion de los Sordos en Mexico. Education of the deaf in Mexico has been spotty and severely underfunded by the government, condemning generations of deaf children to little or no schooling and illiteracy. Historia features 158 pages of Mexican signs with Spanish and English language keys.

Andersen, K. (n.d.) Teaching English as a 3rd language to deaf students.

Andersen, K. (n.d.) Teaching English as a 3rd language to deaf students.

Beauvois, M. H (1992). Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the foreign language classroom: conversations in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 5, 455-463.

Beauvois, M. H (1992). Computer-assisted classroom discussion in the foreign language classroom: conversations in slow motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 5, 455-463.

Brentari, D. Foreign Vocabulary in Sign Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Investigation of word formation. This displays portions of the complete text. This book takes a close look at the ways that five sign languages borrow elements from the surrounding, dominant spoken language community where each is situated. It offers careful analyses of semantic, morphosyntactic, and phonological adaption of forms taken from a source language (in this case a spoken language) to a recipient signed language. In addition, the contributions contained in the volume examine the social attitudes and cultural values that play a role in this linguistic process. Since the cultural identity of Deaf communities is manifested most strongly in their sign languages, this topic is of interest for cultural and linguistic reasons. Linguists interested in phonology, morphology, word formation, bilingualism, and linguistic anthropology will find this an interesting set of cases of language contact. Interpreters and sign language teachers will also find a wealth of interesting facts about the sign languages of these diverse Deaf communities.

Brentari, D. Foreign Vocabulary in Sign Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Investigation of word formation. This displays portions of the complete text. This book takes a close look at the ways that five sign languages borrow elements from the surrounding, dominant spoken language community where each is situated. It offers careful analyses of semantic, morphosyntactic, and phonological adaption of forms taken from a source language (in this case a spoken language) to a recipient signed language. In addition, the contributions contained in the volume examine the social attitudes and cultural values that play a role in this linguistic process. Since the cultural identity of Deaf communities is manifested most strongly in their sign languages, this topic is of interest for cultural and linguistic reasons. Linguists interested in phonology, morphology, word formation, bilingualism, and linguistic anthropology will find this an interesting set of cases of language contact. Interpreters and sign language teachers will also find a wealth of interesting facts about the sign languages of these diverse Deaf communities.

Cabiedas, J. L. M. (1975). El lenguaje mimico. Madrid: Tall. gráficos de la Fed. Nac. de Soc. de Sordomudos de Espan~a.

Cabiedas, J. L. M. (1975). El lenguaje mimico. Madrid: Tall. gráficos de la Fed. Nac. de Soc. de Sordomudos de Espan~a.

Berg, C., Cavanillas, J., Coello, E., Dotter, F., Eisenwort, B., Hilzensauer, M., Holzinger, D., Krammer, K., Krozca, J., van der Kuyl, T., Montandon, L., Rank, C., Roukens, H., Schouwstra, F. and Skant, A. (1999) SMILE: A Sign language and multimedia based interactive language course for Deaf for the training of European written languages, in Preparation for the New Millenium - Directions, Developments, and Delivery: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Technology and Education. Grande Prairie: International Conferences on Technology and Education, pp. 188-190.

Berg, C., Cavanillas, J., Coello, E., Dotter, F., Eisenwort, B., Hilzensauer, M., Holzinger, D., Krammer, K., Krozca, J., van der Kuyl, T., Montandon, L., Rank, C., Roukens, H., Schouwstra, F. and Skant, A. (1999) SMILE: A Sign language and multimedia based interactive language course for Deaf for the training of European written languages, in Preparation for the New Millenium - Directions, Developments, and Delivery: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Technology and Education. Grande Prairie: International Conferences on Technology and Education, pp. 188-190.

Carmel, S. (1982). Published by the author.

Carmel, S. (1982). Published by the author.

Clarke, M. (1993) Vocabulary learning with and without computers: some thoughts on a way forward. CALL, 5, 3, 139-146.

Clarke, M. (1993) Vocabulary learning with and without computers: some thoughts on a way forward. CALL, 5, 3, 139-146.

Kelly-Jones, N. and Hamilton, H. (1981). Signs Everywhere. Los Alamitos, CA: Modern Signs Press. [Contains signs for cities in Mexico.]

Kelly-Jones, N. and Hamilton, H. (1981). Signs Everywhere. Los Alamitos, CA: Modern Signs Press. [Contains signs for cities in Mexico.]

Plann, S. J. Silent Minority: Deaf education in Spain.

Plann, S. J. Silent Minority: Deaf education in Spain.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2003) Challenges to normal foreign language learning: dyslexia, Downs syndrome, deafness, in Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (ed.) The multilingual mind: questions by, for and about people with many languages. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2003) Challenges to normal foreign language learning: dyslexia, Downs syndrome, deafness, in Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (ed.) The multilingual mind: questions by, for and about people with many languages. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Western Oregon University (2000) PEPNet Products Catalog (PDF). "Including Deaf and Hard-of-hearing students in foreign language classes" # 1077.

Western Oregon University (2000) PEPNet Products Catalog (PDF). "Including Deaf and Hard-of-hearing students in foreign language classes" # 1077.

Power Point Presentation with Speakers Notes. Targeting trainers, information is provided to instructors, students, interpreters and service providers to get beyond road blocks to including Deaf and Hard-of-hearing students in foreign language classes. Coming Summer of 2000!

Mailing lists, chat sites, and forums

Mailing lists, chat sites, and forums This is for Sign Language Interpreters working in the educational setting. Este groupo es por los interpretes que trabajan en los escuelas

This is for Sign Language Interpreters working in the educational setting. Este groupo es por los interpretes que trabajan en los escuelas

The mission of the Nat'l Network of Trilingual Interpreters is to provide an online forum through which interpreters for the Latino Deaf community can collectively raise their skill level and expand their cultural knowlege. The NNTI seeks to serve as a central place for relevant questions, answers, and information-sharing, as well as to provide a sense of community and support for trilingual interpreters throughout the United States and Puerto Rico.

The mission of the Nat'l Network of Trilingual Interpreters is to provide an online forum through which interpreters for the Latino Deaf community can collectively raise their skill level and expand their cultural knowlege. The NNTI seeks to serve as a central place for relevant questions, answers, and information-sharing, as well as to provide a sense of community and support for trilingual interpreters throughout the United States and Puerto Rico.

Tri-lingual Interpreters for the Deaf (English/ASL/Espanol). This is a forum for Interpreters for the Deaf and Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing individuals to exchange valuable information. This message board is not limited to Interpreters that are TRIs but for all of those whom benefit from information about Tri-lingual Interpretation.

Tri-lingual Interpreters for the Deaf (English/ASL/Espanol). This is a forum for Interpreters for the Deaf and Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing individuals to exchange valuable information. This message board is not limited to Interpreters that are TRIs but for all of those whom benefit from information about Tri-lingual Interpretation.

Mano a Mano was established for working multilingual interpreters, Hispanic-Deaf consumers, students, people who work closely with Hispanic-Deaf communities, and organizations and entities that support Mano a Mano's views. / Mano a Mano se estableci� para personas con carrera de int�rprete multiling�e, los consumidores Sordos-Hispanos, estudiantes, gente que trabaja cerca con comunidades de Sordos-Hispanos y con las organizaciones y las entidades que apoyen las visiones de Mano a Mano.

Mano a Mano was established for working multilingual interpreters, Hispanic-Deaf consumers, students, people who work closely with Hispanic-Deaf communities, and organizations and entities that support Mano a Mano's views. / Mano a Mano se estableci� para personas con carrera de int�rprete multiling�e, los consumidores Sordos-Hispanos, estudiantes, gente que trabaja cerca con comunidades de Sordos-Hispanos y con las organizaciones y las entidades que apoyen las visiones de Mano a Mano.

Signing Fiesta.

Signing Fiesta.

Web sites

Web sites Bement, L. & C. Quenin. (1998) Cued Speech as a practical approach to teaching Spanish to Deaf and hard of hearing foreign language students. Cued Speech Journal, 6, 40-56.

Bement, L. & C. Quenin. (1998) Cued Speech as a practical approach to teaching Spanish to Deaf and hard of hearing foreign language students. Cued Speech Journal, 6, 40-56.

Cornett, R. O. Adapting Cued Speech to additional languages. As of October, 1993, Cued Speech had been adapted to 56 languages and major dialects. In most of these adaptations, the writer had the assistance of one or more native speakers of the target language. In a few cases he had advice from experts on the phonetic and phonological aspects of the language in question. Other persons produced five of the adaptations (Alu, Malagasy, Maltese, Korean and Polish) with little or no guidance from the writer. [Webmaster's comment: Arabic is included in this list.]

Cornett, R. O. Adapting Cued Speech to additional languages. As of October, 1993, Cued Speech had been adapted to 56 languages and major dialects. In most of these adaptations, the writer had the assistance of one or more native speakers of the target language. In a few cases he had advice from experts on the phonetic and phonological aspects of the language in question. Other persons produced five of the adaptations (Alu, Malagasy, Maltese, Korean and Polish) with little or no guidance from the writer. [Webmaster's comment: Arabic is included in this list.]

Santana Hernandez, R. (Fall 2003). "The role of Cued Speech in the development of Spanish prepositions. American Annals of the Deaf 148, 4, 323-332. Gallaudet University Press

Santana Hernandez, R. (Fall 2003). "The role of Cued Speech in the development of Spanish prepositions. American Annals of the Deaf 148, 4, 323-332. Gallaudet University Press

Torres, S. & Ruiz Casas, M. J. MOC. La Palabra Complementada.

Torres, S. & Ruiz Casas, M. J. MOC. La Palabra Complementada.

Bar-Tzur, D.

Bar-Tzur, D.

Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Spain, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

El Salvador, Mexico, and Spain.

![]() Indigenous signs for countries:

Indigenous signs for countries:

Latin America and Western Europe.

![]() Resources for working with Deafblind people: Argentina, Columbia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Peru, Puerto Rico, Spain, Uruguay and Venezuela

Resources for working with Deafblind people: Argentina, Columbia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Peru, Puerto Rico, Spain, Uruguay and Venezuela

Signing Fiesta. Signing Fiesta teaches ASL through Spanish and English.

Signing Fiesta. Signing Fiesta teaches ASL through Spanish and English.

de la Hoz, P. (n.d.) Los o�dos sordos de Miami. MIDEM.

de la Hoz, P. (n.d.) Los o�dos sordos de Miami. MIDEM.

Donalda Ammons is a Spanish professor at Gallaudet University, and is Deaf. Contact her at

Donalda Ammons is a Spanish professor at Gallaudet University, and is Deaf. Contact her at

Hispanic and Latino Deaf links, Mining Co.

Hispanic and Latino Deaf links, Mining Co.

interpreters-spanishasl. For interpreters who work with English, Spanish, ASL, LSM, and other latin-american sign languages, or are interested in that field.

interpreters-spanishasl. For interpreters who work with English, Spanish, ASL, LSM, and other latin-american sign languages, or are interested in that field.

The mission of the Nat'l Network of Trilingual Interpreters is to provide an online forum through which interpreters for the Latino Deaf community can collectively raise their skill level and expand their cultural knowlege. The NNTI seeks to serve as a central place for relevant questions, answers, and information-sharing, as well as to provide a sense of community and support for trilingual interpreters throughout the United States and Puerto Rico.

The mission of the Nat'l Network of Trilingual Interpreters is to provide an online forum through which interpreters for the Latino Deaf community can collectively raise their skill level and expand their cultural knowlege. The NNTI seeks to serve as a central place for relevant questions, answers, and information-sharing, as well as to provide a sense of community and support for trilingual interpreters throughout the United States and Puerto Rico.

Mano a Mano was established for working multilingual interpreters, Hispanic-Deaf consumers, students, people who work closely with Hispanic-Deaf communities, and organizations and entities that support Mano a Mano's views. / Mano a Mano se estableci� para personas con carrera de int�rprete multiling�e, los consumidores Sordos-Hispanos, estudiantes, gente que trabaja cerca con comunidades de Sordos-Hispanos y con las organizaciones y las entidades que apoyen las visiones de Mano a Mano.

Mano a Mano was established for working multilingual interpreters, Hispanic-Deaf consumers, students, people who work closely with Hispanic-Deaf communities, and organizations and entities that support Mano a Mano's views. / Mano a Mano se estableci� para personas con carrera de int�rprete multiling�e, los consumidores Sordos-Hispanos, estudiantes, gente que trabaja cerca con comunidades de Sordos-Hispanos y con las organizaciones y las entidades que apoyen las visiones de Mano a Mano.

Foreign Language Teaching Forum. Send e-mail to

Foreign Language Teaching Forum. Send e-mail to

Latin American and Carribean studies.

Latin American and Carribean studies.

Learn Spanish. A great way to learn Spanish for free.

Learn Spanish. A great way to learn Spanish for free.

Learn Spanish guide. All about how to learn Spanish and how to speak Spanish.

Learn Spanish guide. All about how to learn Spanish and how to speak Spanish.

Spanish Language Exercises.

Spanish Language Exercises.

Spanish romance. Spanish words, Spanish proverbs, Spanish poems, Spanish recipes, Spanish lyrics, Spanish vocabulary, Spanish phrases, Spanish sayings, Spanish riddles, Spanish stories, Spanish jokes, Spanish schools, Spanish penpals, and much more.

Spanish romance. Spanish words, Spanish proverbs, Spanish poems, Spanish recipes, Spanish lyrics, Spanish vocabulary, Spanish phrases, Spanish sayings, Spanish riddles, Spanish stories, Spanish jokes, Spanish schools, Spanish penpals, and much more.

Spanish WWW sites: Viajes, turismo y empleo.

Spanish WWW sites: Viajes, turismo y empleo.

Vocabulix - Vocabulary trainer and conjugation trainer. You simply choose a lesson in a foreign language and the system will help you to memorize the words of that lesson. Conjugation trainer - With that powerful trainer you can exercise conjugations in various languages. Naturally, different times and forms are supported. If you have a username and if you are logged in, your input and your results will be memorized. You will be able to create your own lessons with the desired vocabulary, as well as measure your progress. German, Spanish and English are currently supported. Soon French and Hebrew.

Vocabulix - Vocabulary trainer and conjugation trainer. You simply choose a lesson in a foreign language and the system will help you to memorize the words of that lesson. Conjugation trainer - With that powerful trainer you can exercise conjugations in various languages. Naturally, different times and forms are supported. If you have a username and if you are logged in, your input and your results will be memorized. You will be able to create your own lessons with the desired vocabulary, as well as measure your progress. German, Spanish and English are currently supported. Soon French and Hebrew.

Argentina

Argentina

Alfabeto dactilologico Argentino.

Sitio de Sordos. Mucha información sobre la sordera y la Lengua de Signos.

El Salvador

El Salvador

Bar-Tzur, D. Indigenous signs for cities: El Salvador.

Mexico

Mexico

Bar-Tzur, D. Indigenous signs for cities: Mexico.

Mexican Sign Language/American Sign Language translator.

Plumlee, M. (1995). Pronouns in Mexican Sign Language.

Davis, C. D. (n.d.) Foreign language instruction: Tips for accommodating Hard-of-Hearing and Deaf students.

Davis, C. D. (n.d.) Foreign language instruction: Tips for accommodating Hard-of-Hearing and Deaf students.

WROCC Outreach Site at Western Oregon University. Foreign Language Resource Links.

WROCC Outreach Site at Western Oregon University. Foreign Language Resource Links.

Diccionario Literario.

Diccionario Literario.

freedict.com: English-Spanish-English dictionary.

freedict.com: English-Spanish-English dictionary.

The human languages page - a comprehensive catalog of language-related Internet resources. Look for Spanish related sites.

The human languages page - a comprehensive catalog of language-related Internet resources. Look for Spanish related sites.

Translatum. Spanish Dictionaries.

Translatum. Spanish Dictionaries.

Travlang's English-Spanish online dictionary.

Travlang's English-Spanish online dictionary.

Travlang's Spanish-English online dictionary.

Travlang's Spanish-English online dictionary.

SpanishDict.com - English to Spanish to English.

SpanishDict.com - English to Spanish to English.

World language resources: Spanish.

World language resources: Spanish.